Revisiting Dead Bodies Under Glass

In 2006 I have had the good fortune to stumble over the Body Worlds Exhibition (in no way associated with the subpar Bodies Exhibit currently in New York) while it was in Philadelphia. This article was the result of my visit.

Some years ago I heard about a peculiar German exhibition consisting of human corpses. The most disturbing exhibit was supposedly that of a dead pregnant woman, on display with her eight-month-old fetus still inside her. In my mind I created a morbid image of a woman’s abdomen cut open with skin flaps stretched and pinned away from the body (a la High School frog dissection) with the fetus inside exposed and grimacing at the viewer. This image was not inspired by horror films, at least not horror films alone, but other exhibitions I have gravitated towards in my travels.

I couldn’t help but include this photo I took of the dancing fetuses from Musée Fragonard

The desiccated specimens of Musée Fragonard in Paris aided my imagination as did the aberrations of Russia’s Kunstkammer. Closer to home (and to the focus of this article) is a single room in Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum where pathologies and other fascinating cases of physical deviation are compiled. What these places all have in common are the displays of human beings, often fetuses, ravaged by disease and malformation, cut open and often flayed. After seeing these three places, where anomalies of nature are collected and variously dissected, no one could blame me for having morbid expectations of Body Worlds: The anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies which is the official title of the German exhibition mentioned above.

Imagine my surprise when what I found was clinical, didactic and even aesthetic. The result of plastination, a preservation process invented ten years ago by Gunther von Hagens, is very different from the still mysterious methods used by Honoré Fragonard during the eighteenth century. The bodies on display were more alike to the models in anatomy classes than to the walking dead in horror flicks.

Body Worlds is currently housed in five galleries of the Franklin Institute Science Museum in Philadelphia and I happened upon it by pure chance during the mini-vacation I took with my significant other during the Thanksgiving break. After shelling out $21.50 (this is with the student discount, but after 5pm the entrance is only $12.75) we found ourselves in a large hall with classically high ceilings. The center of this hall was mostly occupied with glassed in body parts while whole body specimens encircled the room.

The crowd was substantial, but nowhere near a mob as only a certain amount of people is let in every half hour. Both adults and children were present. Some had sketchbooks, a few were talking animatedly in medical jargon and a few were simply gaping in awe. The museums I referred to earlier all had the end result of making me queasy, but here, although some managed to look bored, no one appeared disgusted

The brochure we received at the front desk, and which I will occasionally quote, boasts more than 200 authentic human specimens on display. This includes entire bodies, individual organs, and transparent body slices. The first few to catch my eye were the Muscleman and the Smoker. The muscles of the former are separated from his skeleton and are then propped up by that same frame. The Smoker stands with a cigarette and enough flesh removed to show his blackened lung. Another nearby exhibit, the Basketball Player, with a ball in his hand, his face twisted to show intent, his whole posture that of dribbling towards the hoop is “the most muscular body donor plastinated so far.”

My gaze wandered to the center of the room where the glassed exhibits of various human organs stricken with disease lay next to healthy ones for comparison. Several prosthetics were seen, from limb prosthetics—knee cap thoughtfully popped open for closer inspection—to a prosthetic in the aorta. The next whole body plastinate was split sagittally with superficial muscles removed or lifted and major joints open. Next, the Teacher, one of the many bodies in natural poses, was donated and plastinated after experimental dissections of the pelvis. Leaning forward, he stares happily with eye balls still in orbital cavities, nerves of the face and web of muscles and ligaments extending over the skeleton. Chalk and an anatomy book were very aptly placed in his hands.

The Chess Player sits in contemplation over his chessboard. Aside from making it easier to associate a body in this position with my own (as is suggested by the all-knowing brochure), it illustrated how nerve fibers run through the entire human organism. A few feet away, the Cyclist looms. He looks enormous but is a regularly sized human being sitting astride an oversized bicycle. His was the first body to appear grotesque to me as it was expanded: his muscles, tendons and skeleton were separated to literally allow for the space to contemplate the relationship between organs. Several strips of skin were left to him, which did nothing to alleviate my unease since they looked a lot like the tan leather purse the woman next to me had in her hands.

In case the whole body plastinate of the Smoker was not convincing enough, a glass case containing healthy lungs and heart lay next to the gray diseased organs of a smoker. Next to that were also the lungs of a TB victim and cross sections of thoracic cavities with cancer, emphysema and extensive tumor growth. A hale and hearty organ was also positioned next to an enlarged heart which probably looked a lot like Eddie Guerrero’s heart post-autopsy. It was nearly twice the size of the healthy heart and made me wonder how much change had to happen in the body to accommodate for it. The Organ Man holds out his liver for inspection in one hand and a hefty amount of guts in the other. He also has smoker’s lungs, but on top of that has gall stones and a cancerous liver. Many of the donors have some sort of a pathology associated with their bodies, but then, they all had to die of something.

A small child pressed his face against the glass display of The Blood Vessel Family. He stared for a minute or so at the “mom” with her arm around the “dad” who was holding their “kid” up on his shoulders. With everything but their blood vessels removed they did not become grisly mush but maintained their human shapes. Finally, the young observer explained what fascinated him, “Looook, the peenoos.” Yes, the penis. There is a reason children younger than thirteen are not allowed in without a permission slip and I’m guessing part of this reason is that although post cards and posters of the exhibition hide the genitals, in these rooms when they say that the bodies are displayed whole, they mean it.

The second floor brought on more encased innards and also the longitudinally expanded body. That was followed by the frontal 3-D sliced body which would be an anatomy teacher’s dream come true. Every inch or so marks a separation with the first containing the face and some chest, the last a small portion of the back and buttocks. Certain organs were left to protrude three-dimensionally and the body cavities were made apparent.

“Obesity Revealed” showed fat tissue of a 500lb individual when compared to a 140lb individual and “shockingly revealed the burden that the inner organs endured” and how the excessive fat effectively shortens the life span. The obese person barely resembled anything human while the slim person’s body parts could be easily discerned.

But what is an anatomy exhibit without deformed babies? This curtained off section brought Musée Fragonard (along with Mütter Museum and especially Kunstkammer, where deformed fetuses and even toddlers seemed to be the focus) to mind yet again. On display were fetuses who did not survive due to their extreme defects. They ranged from hydrocephalics, to Siamese twins to a pitifully tiny monstrosity which lacked the top of its skull, had a cleft palate, tangled deformed limbs and its inner organs spilling through a malformed front body wall. The center piece was the eight-month pregnant woman that caused so much controversy. She reclines with a portion of her abdomen cut away to show the only healthy looking fetus in the room curled up inside.

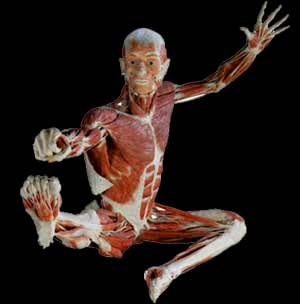

After leaving “the nursery” I approached the Winged Man. His back muscles extended like wings, he rotates, grinning with his skinless smile from underneath a fedora hat. The Kneeling Lady brings to mind a ballerina during a graceful closing to a dance. The Jumping Dancer had his rear body wall together with the brain flipped down to maintain his graceful assent into air during a jump. His is one of the more interesting augmentations: essentially, his whole body is held up in the air by his brain and spinal cord.

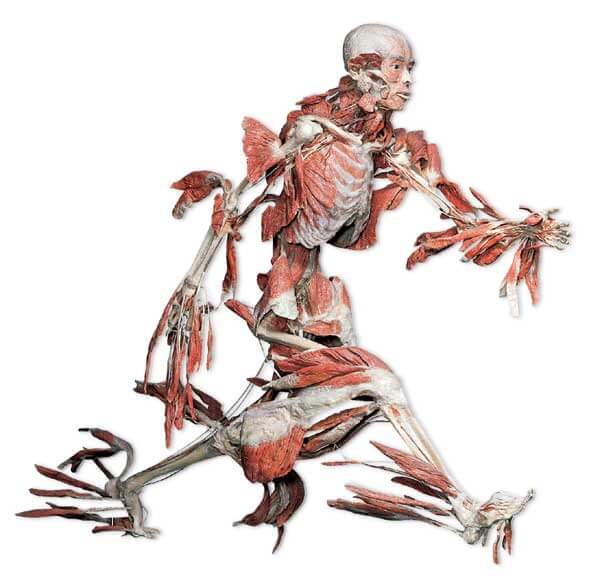

The Skin Man (image at opening of this article) holds his skin out much like a haughty gentleman would hold out his coat to a servant. The sign next to him states that “the skin lends individuality to our exterior; it imparts beauty and age” and that makes me think about how alike so many of these plastinates would look, how impersonal, if not for their dynamic positions. One of the last specimens I see, before the grand finale, is the Runner, with his muscles and skin flapping behind him as if blown out by the wind.

At last, the main spectacle: an enormous plastinate of a man on a rearing horse. “A mountain of flesh and death” in the words of my companion, Beelzy. This too reminds me of Honoré Fragonard who also has a man atop a horse, although in a much less emotional posture. The rider before me holds up his own brain in one hand, and his steed’s in the other. His body is separated until it looks almost like there are two riders. The horse is also somewhat expanded, his already impressive size made shocking.

We left the museum exhausted and anatomically enlightened. The effect was unparalleled, somehow inspiring. We both decided to explore the option of donating our bodies to science. It seems more pleasant to imagine my corpse being lovingly dusted in some museum, than rotting six feet under. But that is a whole other story.

The Body Worlds website has further information on both the continuing exhibition and Gunther von Hagens’ life story which is no less fascinating. Even an extraordinary mind could not have come up with this idea unless extraordinary circumstances shaped it. Information on the process of plastination and body donation can also be accessed from this site.

Body Worlds has been seen by millions of people in 27 cities around the world and it is currently in Montreal. It is scheduled to open in Portland July 7th and is well worth the visit.

Article Copyright © 2007 Eat The Lemons. Foetus de Infants Copyright © 2007 Eat The Lemons, all other images Copyright © 2007 Body Worlds

No trackbacks yet.